Hugh Glass: The Man Who Wouldn’t Die

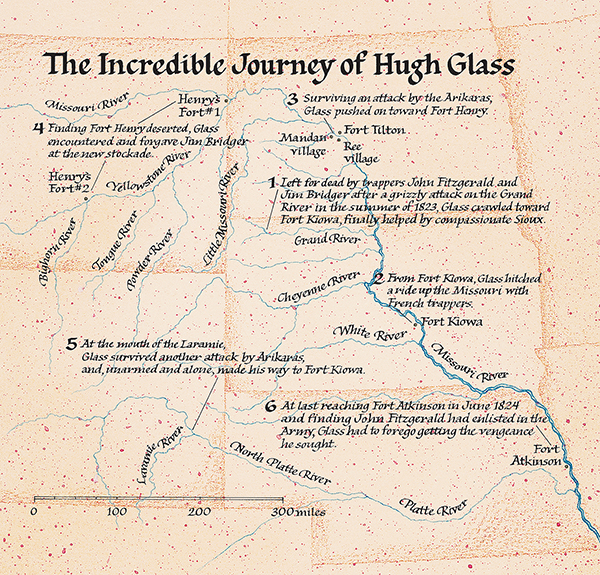

Pirates. Pawnee. A grizzly. A 200-mile crawl. The survival story that still punches through time.

Act I: Baptism by Gunpowder

Born around 1783 in Pennsylvania, Hugh Glass strayed further than most men dared. By the 1810s he had fallen into the grip of Jean Lafitte’s pirates in the Gulf of Mexico, a floating kingdom where a man’s life was worth less than the powder in a pistol.

When Glass tried to escape, the pirates decided to make an example of him. They dragged him before the crew, pressed a pistol to his temple, and pulled the trigger. Click. Misfire. Again. Click. A third and fourth time, the hammer fell on silence. The deck grew restless, bad omens ran deep in pirate blood. To prove the weapon wasn’t bewitched, the man aimed at the sea and squeezed once more. This time the pistol boomed, smoke rolling over the waves. Cursing, the drunken pirate drew his cutlass to finish the job, but Glass slipped into the shadows, vanishing until night gave him cover.

Soon after, their vessel grounded out on the Gulf Coast. The men camped, focused on survival and plotting their next push back to sea. Glass, ragged and desperate, kept to the treeline. He didn’t join them, didn’t risk exposure. He scavenged quietly, living on turtle eggs, shellfish, and seabirds caught with crude clubs. He drank rainwater when the sky allowed and stayed out of sight, a ghost at the edge of their camp.

Among them was another fugitive, his details blurred by history. They weren’t companions; they hardly acknowledged each other. Yet when that man finally left the island to seek his way back to sea, he left something behind for Glass: a knife.

For Glass, it was salvation. With steel in hand he could carve shelters, strip hides, build traps, and craft tools instead of clawing at survival barehanded. He remained on the island alone, honing the quiet stubbornness that would one day make him infamous. When a passing ship finally pulled him off the shore, Glass was scarred, starved, and half-dead—but alive. Already baptized in survival; already marked by the lesson that would define him: grit isn’t about glory. It’s about staying alive when the world has written you off.

Act II: Captive, Then Brother

Westward wanderings pushed Glass into another crucible: capture by the Pawnee. For most frontiersmen, that ended in fire and screams. The Pawnee had their reasons—revenge, ritual, or just plain survival. But Glass’s story bent differently: he wasn’t tortured, he was spared. Why? Historians argue. He may have been adopted to replace a fallen warrior, or perhaps the tribe simply saw something unbreakable in him, a stubbornness that even pirates and starvation hadn’t crushed.

Glass lived with the Pawnee for years, long enough to marry a Pawnee woman and absorb their survival knowledge until it lived in his hands. He learned to track by bent grass and broken spider webs, to move silently across open country where a wrong step could mean death. He learned to hunt with snares and patience instead of the thunder of a musket, and to treat weather like a living enemy—watching the sky, the wind, the birds, and knowing when to move or hunker down. From them, he also learned respect: for the land, for life, for the knowledge that the careless are erased without ceremony.

The pirate turned castaway became something else entirely: a frontiersman with two worlds in his blood. These years would become his greatest weapon—when the bear came, when betrayal buried him, when death circled close, it was Pawnee skills that whispered in his ear: crawl, keep moving, don’t stop breathing until you absolutely have to.

Act VIII: The Final Ambush

Glass returned to the only life he knew: trapping. He never settled down, never planted crops, never chose the safer path. For nearly another decade he lived like a ghost across the frontier—dodging arrows, outlasting winters that froze men solid, and chasing pelts across country so harsh it seemed designed to kill intruders. He carried scars inside and out, a body stitched together by stubbornness and grit. Every step was survival, every season another gamble.

But even the hardest men run out of road. In 1833, along the Yellowstone River, Glass’s luck finally cracked. He and two companions were ambushed by an Arikara war party. These weren’t startled villagers or lone warriors—they were seasoned fighters who knew the land better than any trapper. The attack was swift and merciless. Arrows blackened the sky, spears and musket fire cutting off any escape. Glass fought, but the sheer numbers and precision of the warriors drowned even his legendary resilience. The man who had survived pirates, starvation, betrayal, and the claws of a grizzly bear was finally overwhelmed. It didn’t take disease or old age to bring him down—it took a war party.

Some say that’s the only fitting end Hugh Glass could have had. Death couldn’t creep up on him in bed—it had to meet him head-on in battle, with arrows in the air and the ground running red. His body fell where his life had always been lived: at the edge of survival.

Act IV: The Bear

Summer, 1823 — Grand River country. The cottonwoods were whispering and the wind carried the sweet rot of chokecherries. Glass was ranging ahead of the party, reading sign the way other men read Scripture: a crushed fern, a patch of matted grass, a scuff where a heavy body rolled. He saw the berry thicket a moment before he heard the breath — a wet, rumbling bellows — and knew he’d stepped into a story that rarely leaves survivors to tell it.

A grizzly sow with two cubs rose out of the willows like a landslide learning how to stand. She was already committed, already coming. Glass shouldered his rifle on instinct, cheek to stock, sights blurring over muscle and fur. He touched the trigger. The flint sparked, the pan flashed, the ball hit meat — and it was like poking a thunderhead with a stick. She didn’t stop. She accelerated.

The first hit felt like an axe thrown by God. Claws found his shoulder and chest and picked him up. The world became a wheel of sky, fur, dirt, blood. Her weight crushed the air from his lungs. A paw raked his head and the world went white; another opened his ribs like a careless butcher. Teeth closed on his thigh and his leg answered with a crack. She tore at his throat and for a terrible second he heard a sound that was himself trying to breathe through a hole that wasn’t supposed to be there.

Glass didn’t win anything. He survived seconds. He worked his knife like a drowning man works his arms — not to fight, just to stay at the surface of life a heartbeat longer. The grizzly’s hot breath washed over him, carrion-sweet and wild. He stabbed for eyes, for anything soft, and hit anger, and then more anger. His world shrank to three things: fur, iron taste, and the drumbeat in his skull saying, don’t quit.

His companions heard the shot and the roar and came running, cursing the way men do when fear has a hold of their ankles. They found the sow on him and put more lead in her than a church roof. When she finally folded, Glass was underneath, pinned and making a sound like a torn bellows.

Out here, you don’t get to pick your fights. Sometimes the fight finds you — and if you’re lucky, you die quick. Hugh Glass wasn’t lucky.

They rolled the bear off him and what lay there barely answered to the name of man. Scalp peeled back. Back and arms flayed to corded muscle. A slit below the jaw where breath whistled wrong. Bones speaking through the skin. Someone crossed himself. Someone else said, “He ain’t got an hour,” and meant it.

But Glass was still inside. His eyes tracked them. He blinked when they talked. They stitched him the best they could — coarse thread through skin like wet rawhide, sewing a man back into himself. They packed his wounds, wrapped him in a buffalo robe, and waited for the wilderness to finish what it had started.

It didn’t. All night the camp listened to two things: wolves nosing the dead grizzly, and Hugh Glass refusing to leave his body. Dawn came gray and cold. The bear lay quiet. Glass didn’t.

The moment that made the legend: a man, a sow grizzly, and the thin thread between breath and silence.

Men would later swear you could see daylight through the wound in his throat. They would also swear that when death leaned in to collect, Hugh Glass stared back with the flat, stubborn look of a trapper who’d been shorted on his beaver pelts and wasn’t about to let it slide. The wilderness had delivered its verdict. Glass appealed.

Act V: Buried Alive

The trappers did what they could—they sewed his scalp back on, patched his wounds, and carried him for miles. But he slowed them down, and out here, slow meant dead. Captain Henry ordered two men, John Fitzgerald and a teenage Jim Bridger, to stay behind, watch over Glass until he expired, then give him a proper burial.

They didn’t wait. Convinced he’d never survive, they robbed him of his rifle, knife, and gear—everything a man needed to live. Then they scraped a shallow grave, rolled him in, and left him for dead. Glass was now weaponless, alone, and half-buried. Betrayal is one thing. Being buried alive is another. He had both.

Act VI: The Crawl

Most men would have died right there, but Hugh Glass refused death’s timetable. He clawed out of his grave and began to crawl. For six weeks, he dragged himself more than 200 miles to Fort Kiowa. His throat was half gone, his leg shattered, his body leaking from every seam.

He ate berries, roots, and raw snakes. He drank swamp water and prayed it didn’t kill him faster. Once, he stumbled across wolves tearing apart a buffalo carcass. With nothing but rage and a stick, he drove them off and gorged on the rotting meat. Another time, he splinted his own leg with sticks and rawhide. He packed mud into his wounds to stave off infection. Every mile was another insult to death. Most men beg for mercy. Glass bargained for another inch, another sunrise.

Field note: Today we get annoyed when a water filter clogs. Glass drank puddles and thanked the filth for not killing him. Perspective, folks.

🔥 EDC Survival Keychain Lighter

Rugged, refillable, and always ready — whether you’re opening a beer or sparking a fire in the rain.

⭐️⭐️⭐️⭐️⭐️ 4,700+ reviews

"Built like a tank. Dropped it a mud puddle and it still lit first strike." — Jake R.

"Perfect balance of EDC and survival. This one actually earns a spot in my kit." — Amanda T.

"Lit a fire bunkered down in 30mph wind. Enough said." — Chris D.

⚠️ Only a few left in stock — order before they’re gone!

Grab Yours on Amazon →Act VII: Revenge (Sort Of)

When he finally limped into Fort Kiowa, he was a stitched-together ghost. But rest wasn’t on his mind. Revenge was. Fitzgerald and Bridger had robbed him, abandoned him, and buried him. Now he wanted blood.

He tracked Bridger first—found him young, terrified, and guilty. Glass looked into his eyes and saw a boy, not a killer. He spared him. Fitzgerald was trickier. The man had joined the Army and was hiding behind federal protection. Killing him would have earned Glass a hangman’s noose. So Glass let him live, but not without branding him a coward. Sometimes the worst punishment isn’t death. It’s being forced to live with what you did—and knowing the world knows too.

It wasn’t the ending he wanted, but it was an ending. And maybe, for a man like Glass, outliving your betrayers was the sharpest revenge of all.

Act VIII: The Final Ambush

Glass returned to the only life he knew: trapping. He didn’t retire, didn’t soften, didn’t fade into farming. He went back to rivers, mountains, and the trade that ate men alive. Nearly a decade more he lasted, dodging arrows, enduring winters, and chasing pelts across hostile ground.

But in 1833, his luck finally cracked. Along the Yellowstone, an Arikara war party ambushed him and two companions. Glass fought, but arrows flew thick, and numbers drowned even his grit. The man who had outlasted pirates, starvation, betrayal, and a grizzly bear was finally overwhelmed. It took skilled warriors and overwhelming force to kill him. A fitting end for a man who had survived everything else.

Why Hugh Glass Still Matters

Glass wasn’t a saint. He wasn’t polite or polished. He was a pirate, a castaway, a captive, a husband, a frontiersman, a man chewed up by the wild and spat back out again and again. But his story drives one truth home: when death is certain, grit is the only weapon left.

Glass fought wolves for meat. You can unwrap calories that actually taste good.

Want the full crawl-through-hell story? This book puts you shoulder-to-shoulder with him.

Disclosure: some links are affiliate links. If you buy through them, Grit Gear HQ may earn a commission at no extra cost to you.

Final Word

From a pirate’s misfiring pistol to a grizzly’s claws, Hugh Glass should’ve died a dozen times. He didn’t. He crawled when others quit. He forgave when rage would have consumed him. And he kept pushing until it took a war party to bring him down.

That’s why his story still matters: survival doesn’t belong to the strongest or the smartest. It belongs to the stubborn.

One day your own “bear” will block the trail. Crawl, don’t quit.